Indian Motocycle Riders Global

The history of

INDIAN MOTORCYCLES

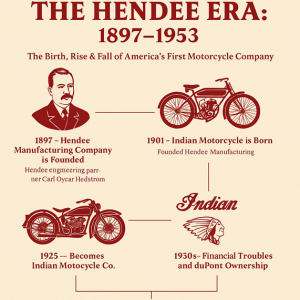

HENDEE

1897 – The Beginning of the Hendee Legacy

- George M. Hendee establishes the Hendee Manufacturing Company to build high-quality bicycles.

- Brands include Silver King, Silver Queen, and later the American Indian bicycle.

- This is the true starting point of the Indian Motorcycle story.

1900 – Hendee Meets Hedström

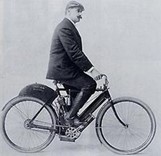

- Hendee sees Oscar Hedström’s motorised pacer bicycle at a racing event in Madison Square Garden.

- Impressed, he hires Hedström to build a motorised bicycle for his company.

The story of Indian Motorcycles is one of innovation, passion, and vision. George M. Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom’s journey from bicycles to motorcycles exemplifies the spirit of American ingenuity.

Hendee’s background in bicycles laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most iconic motorcycle brands in the world. His deep understanding of the mechanics of two-wheelers, combined with his entrepreneurial spirit, allowed him to see an opportunity in the emerging motorcycle market. He brought his expertise to the Hendee Manufacturing Company, which he co-founded with Hedstrom in 1901.

Hedstrom, who was a brilliant engineer, designed the first Indian motorcycle, which became a hit almost immediately. The company quickly grew, thanks to their commitment to quality and performance, helping make Indian Motorcycles a household name. The Indian motorcycle was celebrated for its innovation, style, and power, and became a symbol of American craftsmanship.

Indian Motorcycles was founded in 1901 by George M.Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom.

George Mallory Hendee was born on July 4, 1866, in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Long before motorcycles, he made his name in the booming world of bicycles. Hendee became a successful bicycle racer and later a manufacturer, producing high-quality bicycles under the Silver King, Silver Queen, and American Indian brands. This early business experience gave him the mechanical insight and commercial leadership that would later define Indian Motorcycles.

Role at Indian (1901–1916)

- Co-founder of the Hendee Manufacturing Company in 1901, alongside engineer Oscar Hedström

- Responsible for business leadership, branding, sales strategy, and nationwide dealer development

- Chose the name “Indian” to convey strength, speed, and American identity

- Oversaw Indian’s rapid growth into the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer by the early 1910s

- Guided the company through its golden era of racing success, innovation, and expansion

When He Left

Hendee retired in 1916, three years after Hedström’s departure.

He did not return to Indian during its later decades of ownership changes or decline.

After Indian

After retiring, Hendee lived quietly in Suffield, Connecticut. He focused on farming, philanthropy, and local community activities, remaining respected but no longer involved in motorcycling.

Date of Death

at age 77.

Oscar Hedström was a Swedish-American engineer who joined George M. Hendee in 1900, after Hendee saw one of Hedström’s custom-built motorised pacer bicycles and recognised his engineering talent. Hendee hired him to design a reliable motor-assisted bicycle for the new Hendee Manufacturing Company.

Role at Indian (1901–1913)

- Co-founder of the Indian Motorcycle brand

- Chief engineer and designer of Indian’s first engines and frames

- Responsible for the 1901 prototype and all early Indian engineering innovations

- Helped build Indian into the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer by the early 1910s

When He Left

Hedström resigned in 1913, due to disagreements with new management and frustration over cost-cutting decisions that affected quality. He never returned to the company.

After Indian

After leaving Indian, he lived a quiet life in Portland, Connecticut, occasionally consulting on mechanical projects but largely retired from the motorcycle industry.

Date of Death

August 29, 1960

at age 89.

Alongside George Hendee, co-founded Indian Motocycle Manufacturing Company.

Hendee Manufacturing Company initially produced bicycles. However, when they began producing motorcycles, the company initially adopted the name “Hendee Manufacturing” for their new motorcycle division. The company later became known as Indian Motocycle after they introduced their first motorcycle in 1901.

The name “Indian” was chosen for several reasons, including:

- Symbolism of Strength and Power: The name “Indian” was associated with the Native American imagery of strength, power, and endurance. This aligned well with the company’s ambition to create a powerful, reliable, and competitive motorcycle.

- Marketing Appeal: The name had a strong, exotic appeal, which was seen as an attractive marketing tool. It stood out among competitors and gave the brand an air of prestige and ruggedness.

- Founder Influence: George Hendee himself is often credited with the inspiration for the name. It was a nod to the company’s connection to American history, as the name “Indian” evoked the spirit of the American frontier, making it appealing to customers at the time.

The company officially became “Indian Motocycle” in 1923, solidifying the brand name that would become iconic in the motorcycle world.

The spelling of “Indian Motocycles” without the “r” in the word “motorcycles” is actually a historical quirk tied to branding. In the early 1900s, when the Indian Motocycle Company was founded, the word “motorcycle” was often spelled in a variety of ways, including “motocycle” or “motorcycle.”

Also it paid homage to its beginnings as a bicycle manufacturer who fitted an engine to produce a moto-cycle.

There is also a story that at that time a manufacturer in Spain called ‘Motosacoche’ who was also producing motorcycles and left the ‘r’ out as well which was seen as a unique promotional edge but may have just been a translation error.

At the time, the spelling of words wasn’t as standardized as it is today, and companies would sometimes choose unique spellings to differentiate their brands or simply because it was a common variation in the industry. The Indian Motorcycle Company, under the leadership of founder George Hendee, likely adopted the “Indian Motocycle” spelling as part of their unique branding strategy. It helped give the brand a distinctive identity that set it apart from other motorcycle manufacturers.

Around 1929 the spelling of “motorcycle” became standardized with the “r” as the common form, but Indian continued to use the original form for a while longer.

Early Beginnings:

Indian’s first motorcycle, produced in 1901, was a single-cylinder, belt-driven machine with a 1.75 horsepower engine. It quickly gained attention due to its innovative design and reliability.

Expansion and Popularity:

By 1903, Indian had already become one of the first motorcycle manufacturers in America, and the brand quickly grew in popularity. By 1904, they were producing thousands of motorcycles each year.

In 1907, Indian introduced its V-twin engine, which became one of the most important innovations in the motorcycle industry at the time.

Indian’s reputation for performance grew during the early 1900s, with the company winning numerous races and establishing itself as a leader in American motorcycle manufacturing.

During World War I, Indian, like many other manufacturers, switched to military production. They built motorcycles for the military, which were used for various purposes, including reconnaissance and messenger duties.

After the war, Indian enjoyed an era of growth in the 1920s. The company made significant advancements in motorcycle design, including introducing electric start, hand-operated brakes, and improved springing and suspension systems.

After Hedström Resigned (1913) and Hendee Retired (1916)

Once the two founders were gone, Indian entered a long period of inconsistent leadership, shifting priorities, and strategic missteps. Although the company still produced excellent motorcycles, it no longer had the unified engineering vision that Hedström provided or the business stability that Hendee created.

Late 1910s–1920s: Strong Products, Weak Direction

Indian continued to innovate, releasing:

- The Powerplus (1916)

- The original Scout (1920)

- The Chief (1922)

However, despite strong engineering, the company was becoming increasingly unstable behind the scenes.

Late 1920s – Growing Competition & Mismanagement

By the late 1920s:

- Harley-Davidson was rising rapidly

- Cheaper European imports were entering the U.S. market

- Indian’s leadership problems created inefficiency and high production costs

Indian began to lose market share and struggled to find a consistent direction.

1930 – Bankruptcy & the duPont Acquisition

The Great Depression devastated the motorcycle industry. With plummeting sales and rising costs, Indian filed for bankruptcy in 1930.

This crisis triggered a turning point:

The duPont family stepped in and saved Indian.

Éleuthère Paul du Pont (“E. Paul”), a lifelong engineer, tinkerer, and motorcycle enthusiast, had already been indirectly connected to Indian through his brother Francis, who had invested $300,000 in 1923. Faced with the near-collapse of that investment, the family acted:

DuPont Motors, a company known for its beautifully crafted luxury cars (1919–1931),

was merged with Indian Motorcycle.

E. Paul du Pont became the president of Indian.

DuPont Motors had produced only ~600 luxury automobiles in its lifetime — beautifully built, but too costly to survive the 1929 crash. E. Paul wisely shut down automobile production in 1931 to focus entirely on Indian.Paul du Pont – The Man Who Rebuilt Indian

Paul was not just an executive — he was a hands-on motorcycle enthusiast:

- Built his own motorized bicycles as a teenager

- Owned an early 1908 Indian Camelback

- Worked with lathes and machinery personally

- Believed motorcycles were becoming leisure machines, not just tools

His Leadership Philosophy

- Paul made bold changes at Indian:

- Motorcycles for Enjoyment, not Utility

He recognised that the future rider wanted:

- Style

- Comfort

- Speed

- Personality

- Racing as Advertising

DuPont focused heavily on AMA Class C racing, helping revive Indian’s competition presence.

- Styling & Design Innovation

He hired legendary stylist Briggs Weaver, who created:

- The sweeping, deeply skirted fenders

- The iconic Art Deco curves

- The ‘Indian head’ insignia

- The design language that STILL defines Indian today

- Bold Colours from DuPont Paint

DuPont Chemical invented fast-drying nitrocellulose lacquer in the early 1920s.

Under duPont ownership, Indian became available in 24 bright colours, a revolution compared to the “any colour as long as it’s black” reality of earlier manufacturing.

This gave Indian unmatched visual appeal in the 1930s.

Production Revival and Racing Success

Under duPont ownership:

- Quality control improved dramatically

- The Scout, Chief, and Four reached peak refinement

- Indian’s racing team achieved real success again

- Steven du Pont (E. Paul’s son) helped engineer the Big Base Racing Scout

- Sales climbed, and profits finally returned

By 1938, Indian was profitable again — hugely so.

Indian’s 1938–1940 models remain some of the most recognizable motorcycles ever built.

Indian in WWII (1940–1945)

- Paul du Pont oversaw Indian’s wartime production.

Though Harley-Davidson’s WLA was selected as the U.S. primary military bike, Indian produced:

- 741B – 500cc military Scout

- 640B – Chief-based military motorcycle

- 841 – Experimental shaft-drive V-twin inspired by the BMW R75 (only ~1000 built)

The 841 was E. Paul’s personal favourite; he put thousands of miles on his own machine.

The End of the duPont Era

As WWII ended:

- Indian was profitable

- Demand was high

- The styling and engineering were admired worldwide

But E. Paul du Pont’s health was failing, and the profitable factory became attractive to investors.

The duPont family stepped away — though their passion for motorcycles continued.

They kept Indian alive in the 1930s — without them, Indian would not have survived to see WWII or inspire later generations.

In 1945, Indian was sold to an investor group led by Ralph B. Rogers.

Transition to the Decline Under Rogers (post-1945)

In 1945, duPont sold Indian to Ralph B. Rogers and Torque Engineering.

Rogers wanted to modernize Indian, but his strategy was flawed.

After duPont ownership ended, Ralph Rogers made catastrophic decisions:

- Focused on lightweight vertical twins

- Reduced investment in the big V-twin Chief while betting heavily on the vertical twin program

- Rushed untested designs to market

- Lost dealer and rider confidence

This led directly to Indian’s long decline, culminating in the company’s closure in 1953.

He:

- Cut back production of the big Chief

- Bet everything on the new vertical twin line

- Invested heavily in untested designs

- Attempted a global expansion Indian could not support

These decisions drained Indian’s finances during a critical time.

1948–1949 – The Desperate Vincent–Indian “Vindian” Project

Indian attempted a bold partnership with Vincent HRD to create a high-performance hybrid motorcycle for the U.S. market.

Vincent HRD in the UK, under Phil Vincent and chief engineer Phil Irving, had developed the world’s fastest production motorcycles (the Series B Rapide in 1946, followed by the 1948 Black Shadow). However, Vincent was a small-volume specialist maker, struggling financially and keen to expand into the lucrative American market.

1948–1949 – The Idea

By 1948, Indian’s big Chief twins were outdated, heavy, low-revving, and inefficient compared to modern OHV designs. The 74ci (1,200cc) flathead engine was heavy and underpowered compared to British and European OHV designs. Ralph Rogers wanted to modernize Indian’s lineup with lightweight OHV vertical twins (the 500cc Scout, 440cc Warrior, etc.), but American riders and dealers still demanded big displacement and speed.

That’s where the collaboration idea was born:

- Fit Vincent’s 998cc OHV V-twin engine and gearbox into the proven Indian Chief chassis.

- Retain the iconic Indian styling (skirted fenders, Indian tank, comfortable American ergonomics).

- Sell it in the U.S. as an “Indian” with world-leading performance — potentially leapfrogging Harley-Davidson.

1949 – The Prototypes

In early 1949, Vincent engineers built two prototypes at their factory in Stevenage, England:

- Vindian Prototype #1 – A Rapide engine installed in a Chief chassis, keeping most of the Indian cycle parts intact.

- Vindian Prototype #2 – A more refined machine, with Vincent transmission, electrics, and Indian sheet metal.

Both were shipped to the U.S. for testing and evaluation by Indian management.

Performance was strong — far beyond the sidevalve Chief — but there were concerns:

- The bikes were complex and costly to build.

- Import duties and transatlantic logistics made production expensive.

- Indian’s finances were already weak, and Vincent couldn’t bankroll mass production.

Collapse of the Project

By late 1949, the project was shelved. Indian doubled down on its own lightweight vertical twin program (the Scout/Warrior line), but these proved unreliable and failed in the marketplace. By 1953, Indian ceased motorcycle production entirely.

Vincent fared no better — production ended in December 1955, after just 27 years of operation.

Survivors

- Of the two Vindians built, at least one is known to survive. It has appeared in private collections and occasionally in museums. The fate of the second is uncertain — some accounts suggest it was dismantled.

Two prototypes were built, but:

- Cost

- Logistics

- Indian’s weak financial state

- Vincent’s limited production capacity

…meant the project never reached production.

This was one of Indian’s last serious attempts at regaining its former glory.

1950–1952 – Collapse Accelerates

Indian’s new vertical twins failed catastrophically in the marketplace:

- Fragile engines

- Constant mechanical failures

- Warranty claims

- Manufacturing inconsistencies

- Poor dealership support

Meanwhile:

- Harley-Davidson dominated America

- Triumph, BSA, and Norton flooded the U.S. with fast, affordable imports

- Indian’s Chief was outdated, built in low numbers, and expensive

Indian no longer had a competitive product.

1953 – Indian Ceases Production

After years of losses, shrinking sales, and failed new models, Indian Motorcycles:

- Stopped all production in 1953

- Went out of business as a manufacturer

- Left behind only its name and a legendary legacy

The Springfield era — the true, original Indian Motorcycle company — ended permanently.

Legacy

Although the Indian name resurfaced many times over the next 50 years under various owners, the original company created by Hendee and Hedström effectively ended in 1953, marking the closure of one of the most iconic motorcycle manufacturers in history.

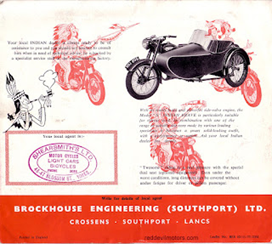

BROCKHOUSE

The first resurrection of Indian — and the moment when everything changed.

When the original Indian Motocycle Manufacturing Company closed its doors in 1953, the factory in Springfield fell silent never to be used today only parts of the foundations left today with no signs it ever was there — but the name Indian did not die.

Instead, it entered a strange and complicated chapter under the control of a British company called Brockhouse Engineering.

This period reshaped the Indian brand forever, marking the first time the Indian name was separated from the motorcycles that made it legendary.

Who Were Brockhouse?

Brockhouse Engineering (Southport, England) was a large post-war industrial supplier known for producing:

- Motorcycles

- Power units

- Sidecars

- Industrial equipment

They were not a premium motorcycle builder.

Instead, they specialized in mass production and contract manufacturing, often supplying components to companies that needed wartime-style efficiency.

Brockhouse was the parent company behind Clyno, James, and Dot motorcycles — modest commuter machines, not American-style V-twins.

Why Brockhouse Bought Indian

After Indian collapsed financially in 1953, Brockhouse acquired:

- The trademark rights

- The dealer network rights

- The ability to market motorcycles under the Indian name

But they did not buy:

- The Springfield factory

- The Chief/Scout tooling

- Any meaningful manufacturing capability in the U.S.

Their goal was simple:

Use the Indian brand to sell motorcycles they did not build.

This was the birth of “badge engineering” in Indian’s history.

Rebadging Royal Enfields (1955–1960)

The most significant move Brockhouse made was to partner with Royal Enfield of Redditch, England.

Royal Enfield built:

- Bullets (350cc / 500cc singles)

- Meteor and Super Meteor twins (500–700cc)

- Constellation 700cc twins

These bikes were solid British machines — but they were not Indians.

Brockhouse imported Royal Enfields to the United States, rebadged them, repainted them, and sold them as “Indian” models:

The Royal Enfields that Became “Indians”

- Indian Brave → Royal Enfield 250 single

- Indian Prince → Royal Enfield 350 Bullet

- Indian Westerner → Enfield 500 Twin

- Indian Fire Arrow → Enfield 250

- Indian Trailblazer → Enfield Super Meteor 692cc

- Indian Apache → Enfield Constellation 700cc

- Indian Chief → Enfield 700cc twin with big fenders to mimic the old Chief style

The “Chief” of this era had no relation to the legendary 1922–1953 Chief except the name and some cosmetic fender work.

How Riders Reacted

American riders who remembered Springfield’s powerful V-twins were confused — and many were disappointed.

The Brockhouse “Indians”:

- Looked British

- Felt British

- Had British ergonomics and engineering

- Were smaller, lighter, and less powerful

- Lacked the iconic Indian personality

Dealers struggled.

Customers were irritated.

And the Indian identity was watered down.

This era planted the seeds of the brand’s long identity crisis.

Attempts to Keep the Brand Alive

Brockhouse did invest in:

- Keeping the U.S. dealer network operating

- Producing accessories

- Offering sidecars and small-displacement commuter bikes

But they were not trying to rebuild Indian — only to monetize it.

Several U.S. distributors complained that Brockhouse supplied:

- Inconsistent parts

- Unreliable shipments

- Poor marketing support

Enfield’s British bikes were well made, but the rebadging strategy failed to resonate with Americans.

The End of the Brockhouse Era (1960)

By 1960:

- Sales had collapsed

- Dealers revolted

- The rebadged Enfields were not selling

- Brockhouse lost interest in the brand

Brockhouse relinquished control of the Indian name, ending their seven-year run.

No Indian motorcycles — U.S.-built or otherwise — would be produced again in any recognizable form for the next several years.

This ended the first failed resurrection.

What this part of the history of Indian did was keep the name alive and Indian became a brand not a manufacturer. The name might have been lost altogether without this era.

© IMRGlobal 2025